The Felshtin Society is named after a Ukrainian shtetl called Felshtin, which today is the Ukrainian town of Hvardii’ske. The Felshtin Society began as a benevolent society organized in 1905 in New York City and it’s still active today. One of the most notable of its ongoing humanitarian efforts over the past 113 years is the refuge and relief that this society provided to the survivors of the 1919 pogrom in Felshtin. Six hundred Jews perished in that brutal pogrom.

In April of 2019 the Felshtin Society will hold commemorative events to mark the centenary of this tragic historical event. Last March, we spoke with the president of the Felshtin Society, Alan Bernstein, who told us about the society and its plans for these commemorative events. Recently the society announced some exciting new developments, which Alan has kindly agreed to share with Nash Holos listeners. We spoke by phone from his office in New York.

In April of 2019 the Felshtin Society will hold commemorative events to mark the centenary of this tragic historical event. Last March, we spoke with the president of the Felshtin Society, Alan Bernstein, who told us about the society and its plans for these commemorative events. Recently the society announced some exciting new developments, which Alan has kindly agreed to share with Nash Holos listeners. We spoke by phone from his office in New York.

Pawlina: So Alan, welcome back to Nash Holos.

Alan Bernstein: Thanks very much. I appreciate your having me back.

Pawlina: Well it’s great to have you! This story is really fascinating to me and I’m excited to hear about the new developments. But just to refresh our listeners’ minds for those maybe who didn’t catch the first interview, tell us a little bit about the Felshtin Society and the history behind it that is bringing these commemorative events to the fore next year.

Alan Bernstein: Well, the Felshtin Society was begun as what was called a landmanschaft organization that was founded originally in 1905 in New York. It was basically something that people pull together in order to be able to, first of all, deal with the issues of burial that they had a hard time dealing with in New York at that time because there were no consecrated Jewish cemeteries. There were very few and there needed to be more. So they got together and these people bought a plot of land in Staten Island, other groups in Long Island or Queens and some of the outlying areas. And that was one of the primary reasons for them to be together, was to have a burial society. And then there were other things as well. Of course it was social, there was support. And then after the pogroms happened in 1919 they became much more of a benevolent society because they collected money not only for the people who were displaced from their homes and lost everything and tremendous number of orphans that were left after their parents were killed in Ukraine and Belarus and in other parts of what was at one point the Russian empire.

Alan Bernstein: Well, the Felshtin Society was begun as what was called a landmanschaft organization that was founded originally in 1905 in New York. It was basically something that people pull together in order to be able to, first of all, deal with the issues of burial that they had a hard time dealing with in New York at that time because there were no consecrated Jewish cemeteries. There were very few and there needed to be more. So they got together and these people bought a plot of land in Staten Island, other groups in Long Island or Queens and some of the outlying areas. And that was one of the primary reasons for them to be together, was to have a burial society. And then there were other things as well. Of course it was social, there was support. And then after the pogroms happened in 1919 they became much more of a benevolent society because they collected money not only for the people who were displaced from their homes and lost everything and tremendous number of orphans that were left after their parents were killed in Ukraine and Belarus and in other parts of what was at one point the Russian empire.

After the Russian revolution, there were just thousands of kids all over the place that needed to be housed and clothed and fed and educated. So there were orphanages that sprung up all over the place. And these landmanschaft organizations were very instrumental, not only in collecting money directly among their own members and sending the money back and making visits, but they also were instrumental in connecting with important Jewish organizations like HIAS [Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society] and Jewish Defense Counsel and things like that. They that were also very supportive of these efforts to make sure that the kids had a place to live and, and adequate clothing and food and education. So, that’s where it started. And then in the 20s and the 30s, they were more focused on social activities and developing support networks that people who were building businesses and, who were interested in doing a variety of other things.

And eventually in the late thirties came to the point where they decided that it would be a very important thing to write a book. So the Felshtin Society’s main focus of existence at that point became the writing of the book from the early to mid thirties. And it was published in 1937. And what happened was people decided that it was okay for each of them to contribute a chapter. So some people contributed more than one chapter and some contributed other things aside from the written word. But basically they got together and they put this wonderful book together, which we understand from a number of scholars who look at this type of literature and who feel that our book—the Felshtin Yizkor Book is what it’s called—is a very strong model of the kind of literature that was produced in response to these events. And then of course, when the Holocaust came and the Germans invaded this part of the world, the rest of the Jews who were living in the town were slaughtered and buried in a mass grave in the town.

So, the Society persisted pretty much on a very regular basis through the 70s. And then people began to die off and the original members were no longer interested or no longer capable of participating. So things really died off until about the nineties when we began to become much more interested in the book and the translation of the book, which was written largely in Yiddish, and trying to see what we can do to maintain the society. So we had 10 year anniversary reunions, one in 1999 and one in 2009. And five or six years ago, we decided that it was very important for us to think about what we could do to commemorate the centennial of the pogrom that occurred in Felshtin. And we began talking about it with a number of people including the YIVO Institute and the Museum of Jewish Heritage and other significant Jewish cultural organizations in the city.

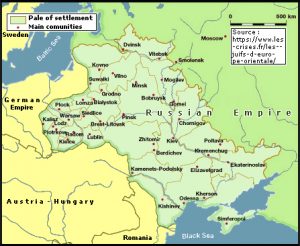

And slowly but surely came up with the picture of that possibility as something that really the Felshtin Society was pretty much the only functional, or one of the main functional organizations of its kind, that was left and it was really going to be up to us to not only shine some light on the events that happened in Felshtin, but really to look beyond that and look at the events that occurred throughout Eastern Europe at that time. Again, in Ukraine and Belarus, Poland, Lithuania, you know, it was just a very wide range of geographical area where these things took place.Pawlina: Yes, it was called the Pale of Settlement, right?

Alan Bernstein: Yes, it was called the Pale of Settlement until I think till 1912 or something like that.

Pawlina: 1917. It was the Provisional Government…

Alan Bernstein: 1917 okay. That’s when it was. Yes. So this is pretty much where we came and we then began to put together a program that we thought was going to be meaningful. And we’ve been working on it now steadily for about two years and we’re looking forward to having our event on April 14th of 2019 at the Center for Jewish History in Manhattan right off Union Square. It’s a very wonderful place. It’s a beautiful building that houses the Center for Jewish History itself, as well as the YIVO Institute and there’s a cultural center. It’s a really wonderful repository of valuable information—documents from the old world, documents from the United States that people brought over. It has an enormous archive. And it has been a great source of support and a tremendous resource to us going forward and trying to put this event together.

Pawlina: Oh, it sounds like it’s going to be an incredible event and you’re connecting up with people all around the world pretty much to commemorate it as well, and to remember. This is a story that kind of got—become almost cliched after Fiddler on the Roof. You know, people kind of knew there were these pogroms back—ancient history, right? But it’s important to not just consign these things to the dustbin of history because it’s important to remember. History can repeat itself. And we may be, for all we know, on the cusp of of repeating terrible mistakes of history ourselves. So it’s a very good thing to be commemorating these events as you’re doing now. So before we go on, I just wanted to ask you for some clarification. There’s a term that you mentioned, land man…

Alan Bernstein: Landmanschaft?

Pawlina: Right. What does that mean?

Alan Bernstein: Landmanschaft is basically, neighbors. A Landsmann is a neighbour, is someone who comes from your town or your neighbourhood, or from your shtetl in that case. So the landmanschaft organizations were groups of people who gathered primarily around the towns that their families came from.

Pawlina: Okay. All right. So let’s go back then to the commemorations that are going to be taking place in April.

Alan Bernstein: Yes, in Manhattan.

Pawlina: Okay. So you’ve been planning this, you said actually you started thinking about this six years ago, but plans have actually been going on for the past two years. And so you’ve got the location set and you’ve got the date set and you’re planning events as well. But you’ve had something recently … you put out this press release. So a really interesting and exciting development has happened in Ukraine. So tell us about the connection there and the actual site of this town, which no longer exists, right? Felshtin to no longer exists.

Felshin’s Last Jew: Polina Lerner in Hvardiiske (formerly Felshtin) in 1957. Photo: Felshtin Society www.Felshtin.org

Alan Bernstein: Well it’s fascinating because we don’t really know how it happened. So we’re kind of doing our own private detective work to find out exactly how this came to pass. We suspect that one of our members, one of our Felshtiners, who actually was born in Felshtin and who grew up in Felshtin and whose family survived even though they were Jewish, because they passed for Catholic. This lady, her name is Polina Lerner, went back to visit Felshtin this past spring and I believe it’s as a result of her visit to Felshtin that the local Catholic priest got involved.

And so I think that she happened to, when she was there, meet with the principal of the school, a fellow by the name of Yuri Federov and they talked about what kind of sustained activities there could be that would bring the history, the full history of the town to light for the school children. And they talked about the possibility of establishing a museum type display in one of the corridors of the school where they have glass enclosed display cases. And, wouldn’t it be wonderful if we could do a visual depiction of what the town was like a hundred years ago and talk about the Jews and talk about how things came to pass. Now that they had that discussion.

I believe that that discussion spilled over to the Catholic clergy. Then we got this wonderful letter from Father Piotr who said to us that we’re going to have a memorial on the day of the pogrom where we pledge to have 600 people with candles lit in the town. And we think that’s a very powerful thing and it’s a wonderful message for the town to send and for the church to become involved in and for us to be able to feel that our ancestors will be remembered in that way on that day.

Pawlina: Yes.

Alan Bernstein: So it’s a really wonderful thing and we’re hoping to be able to work with other priests in the local area and maybe even, get it to spread a little bit. For instance, Khmelnitsky, which is only about 12 or 15 miles away, might be another town where we could attempt to reach out to the local clergy and see if they wouldn’t participate. Khmelnitsky itself has a synagogue that we were establishing communications with, but we’re hoping that the activity Father Piotr will spread to other communities that suffered similarly in those days.

Pawlina: Oh, what a great gesture of reconciliation.

Alan Bernstein: Yes, I think so.

Pawlina: And maybe can we heal wounds of the past and move forward as I think people hoped over the centuries. What is the name of this church?

Alan Bernstein: It’s Saint Wojciech parish.

Pawlina: Okay. And it’s Roman Catholic?

Alan Bernstein: Yes. And Father Piotr is also inviting the Orthodox, the eastern Orthodox clergy, to participate as well. So it’s not only going to be Catholic.

Pawlina: That’s amazing.

Alan Bernstein: And of course we’re hoping that we’re going to be able to get the synagogue in Khmelnitsky involved. We’ll see what happens!

I’ve been speaking with Alan Bernstein, president of the Felshtin Society in New York. Next week, in part two of this interview, Alan will share more details about the society’s phenomenal connection with a school and a Catholic church in Ukraine, eager to help shed light on their town’s lost Jewish heritage. Meanwhile, for more information about the Felshtin Society and the history of the Jewish shtetl Felshtin, visit their website, www.Felshtin.org. So until next time, Shalom!

Ukrainian Jewish Heritage is brought to you by The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter based in Toronto, Ontario. To find out more visit their website (here) and follow them on Facebook and Twitter. Transcripts and audio files of this and earlier broadcasts of Ukrainian Jewish Heritage are available at their website, Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.org as well as at the Nash Holos website.

![]()

Tune in to the Vancouver edition of Nash Holos Saturdays at 6pm PST on CHMB Vancouver AM1320 or streaming online. As well, the Nanaimo edition airs on Wednesdays from 11am-1pm on air at 101.7FM or online at CHLY Radio Malaspina. As well the International edition airs in over 20 countries on AM, FM, shortwave and satellite radio via PCJ Radio International.