Rhea Clyman is a journalist who is little known today in the Jewish or Ukrainian communities, or for that matter, by Canadians in general. But in her day she reached international acclaim for her coverage of the Soviet Union, including the 1932-33 man-made Ukrainian famine known as the Holodomor, and the rise of Nazi Germany.

Jars Balan is the director of the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Alberta where he is also the coordinator of the Kule Ukrainian Canadian Studies Center.

During his research on the Holodomor, Jars stumbled onto Rhea’s reports. He was instantly intrigued by her story and began to research her life and work. He has since spoken about Rhea Clyman extensively, and is currently working her biography.

He kindly agreed to tell us about his work, as well as the work of this remarkable Jewish Canadian journalist.

Pawlina: Jars, thank you so much for joining us.

Jars Balan: Thank you for having me.

Pawlina: Now… Rhea Clyman, I just recently found out about her. How did you find out about her? I mean, it was during your research, but was there something specific? Because I had done a lot of research, although not as much as you because I’m not an academic, but I had never heard of her.

Jars Balan: Well, this is a serendipitous find in the course of doing other research. The Kule Ukrainian Canadian Studies Center at CIUS was doing research on the history of Ukrainians in Canada in the interwar period. We went to archives and various sources—the Edmonton newspapers, the Edmonton Journal, and the Edmonton Bulletin—for certain years and the interwar years. I specifically chose 1932, 33 because I wanted to know what did the Canadian mainstream newspapers report about what was going on in the Soviet Union.

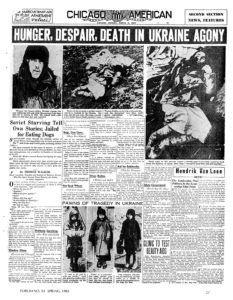

The impression is that the community felt that the Soviets did such a good job of suppressing the information that nobody knew about the famine until after the Second World War, and when immigrants came from Central and Eastern Ukraine and areas that were affected by the famine who started writing and talking about their experiences. What we discovered shocked us actually, that there was lots of coverage about the Soviet Union in the Edmonton Journal and the Edmonton Bulletin. Those we had to go through looking at microfilms, hiring somebody to go page, by page, by page and pull all the Ukrainian content. But the Toronto Star and the Globe and Mail are now available as searchable databases.

We went into those and found an incredible amount of information. I mean, in the Toronto Star and The Globe, The Star in particular, almost every day of the week there were five, six, seven items related to the Soviet Union. Front page news story, a couple of a human interest stories, a letter to the editor, an editorial or an opinion piece, all kinds of stuff.

And in amongst all of that there were lots of references to the disaster of collectivization and the problems with the five-year plan as well as all kinds of spin that presented it all in a very positive light. So there was a mixture of good and bad.

When that happened, I also began to realize that, depending on the newspaper, the spin was different. The Toronto Star was very liberal and soft on the Soviet Union. The Globe was more conservative. And I thought, well, at that point Toronto had five newspapers, including the Toronto Telegram. I then hired a couple of students of Trent University and said, “Could you go through 1932, 33 page by page because it’s not available, it’s searchable, but it’s looking at microfilm.”

Well, these students worked for a month or so and then threw the towel in because you have to really love that kind of research to sit there going through newspapers. I do. But one of the students found three or four articles in what was obviously a series by Rhea Clyman, who I’d never heard of.

After the students threw in the towel, I managed to find some money and I hired my colleague and friend, Dr. Serge Cipko, who was the assistant director of CIUS to go through first of all 1933, and that’s where we found 21 articles by Rhea about this incredible trip she made through the famine lands as it was billed. Then I had him go back to 1932 and there was another 21-article or 22-article series about her trip that she made just before that to the far North and seeing the prisoners being used as slave labor in the mines and in the forests. She wrote a series of articles about that. That was where it started. Then from that I began doing more digging to find out about her background—who she was, how she ended up there. And the story just became more and more and more interesting.

Pawlina: She was a very interesting person. She was born in Poland, I guess as a child, came to Canada in that first wave of immigration from the Austro-Hungarian empire. She started out life with a disadvantage.

Jars Balan: Yes. She came from a very poor immigrant family. We’ve learned a little bit more literally in the last few weeks, even. Her father and mother emigrated in 1906 when she was two years old. And she had two older brothers who were with her as well. They settled in the North end of Toronto, just north of Dundas Street and just off Young Street, just north of the downtown in a very poor neighborhood. I’ve got photographs of what the street she lived on looked like in those days. Slum housing, factories right next door, this kind of thing.

They were dirt poor. They moved after a number of years. But her early years were very difficult because she was six years old and she fell under a street car trying to get on a street car following a Victoria Day parade. They amputated her left leg below her knee. So she was in and out of hospital for months. Actually years because of course as she was growing, they have to adjust the prosthesis and stuff. But she was a tough little girl and also obviously very naturally bright.

One of the people who visited her was a man named Robertson who was the editor and the publisher of the Toronto Telegram. He was also philanthropist who supported Sick Kids Hospital where she was. He began talking with her and he asked her once, “What would you like to do when you grow up?” She said, “I want to be a writer, like a journalist.” He gave her a copy of the Bible, the King James edition I guess, and said, “Read this, you’ll learn everything you need to know about writing.”

But she was very determined and he looked in on her periodically. Then the next horrible thing that happened to her was her father died when she was 11. And that left the mother now with six kids, another three who were born in Canada. Rhea, at the age of 11, went to work in a factory and was taking some classes in the evening or whatever. Basically managed to then take some secretarial courses when she was a teenager and learned how to be a stenographer secretary, a practical thing so she could help support the family.

I’ve learned since that her mother was actually illiterate. I just got a few weeks ago a copy of an attempt… she applied to get a Canadian birth certificate in 1927 just before she was going to Europe. And on it the first thing is she already spelled her name C-L-Y-M-A-N but the original spelling was K-L-E-I-M-A-N. They scratched out her C-L-Y name on it. On the form, her mother who signed with an X, because it was submitted on her mother’s behalf, it stated that she was born in Toronto and delivered by a mid-wife, probably to simplify matters. So she got a birth certificate saying that she was born in Toronto when in actual fact she wasn’t. The application also indicates that her father worked as a junk dealer.

So we’re talking about a woman who grew up in very difficult circumstances but was very determined. And she was ambitious, and she wanted to see the world. So she moved in 1925 to New York and got a job working for a psychoanalyst. I have a feeling she was either a receptionist or just a secretary. She certainly wasn’t doing psychoanalytic work. But it was probably while she was in New York that she got involved with radicals of her generation.

This was a time when there was all kinds of propaganda about how wonderful the Soviet Union was, women had equal rights… And so a lot of young people—and many of them Jewish women too—were attracted to it. And she set as her goal, she wanted to go see this new society that was being born across the ocean. She managed to get a job first in London, working for, of all things, the Alberta Government—

Pawlina: In London?

Jars Balan: Yeah, doing public relations. She worked out of Canada House. The Alberta government had an office then, as I believe it still does now, that promotes tourism, investment, the awareness of Alberta and Great Britain. So she worked there for a year. And this was a great job when you think about it. She’s gone from New York to London. It’s an exciting big international capital.

Pawlina: Yeah, no kidding!

Jars Balan: But her goal was to go East. So she applied and got a student visa to study French in Paris, French language courses at Sorbonne for three months. And at the same time was teaching English on the side to help pay her expenses. After her student visa ran out, she didn’t go back to London—much to the consternation of her friends who thought she was crazy. You’ve got a great job here, you’ve got friends here and stuff, but she thought it was too easy.

She pushed on to Germany. Now this is 1928 now, and the Nazis haven’t come to power yet. But they’re surging in popularity and there’s clashes between them and the left…the Bolsheviks, the Communists. It’s a very dynamic time, exciting time. She picked up a bit of German, and while she was in Germany she got news that the visa that she applied to go to the Soviet Union finally came through. So she got a copy of her visa in Berlin and jumped on a train on December 28, 1928 for Moscow.

Now, there’s evidence that she was actually a member of the Communist Party by this time. She might’ve actually joined it in New York or certainly in Britain. There’s a reference in some intelligence intercepts who were being a courier for the communist party activists there. That certainly would have helped her get permission to go to the Soviet Union. But she got her papers. She shows up in Moscow…she’s 24 years old, she doesn’t speak the language, she knows nobody. She hasn’t even booked a hotel or anything. And she’s got $75 or 15 pounds Sterling to her name. So not a lot of money.

She’s wandering around the main train station. And this guy notices her and sees that she could use some help. He steered her across the street to a hotel where there was a correspondent with a Chicago newspaper who was there with his wife. She spent the first night sleeping in their bathtub. And they helped her find a place to stay and it looks like they also introduced her to Walter Duranty of the New York Times. The notorious Mr. Duranty.

Pawlina: I was just going to say, Jars, that one thing in common was they were both amputees. But their reportage really diverged.

Jars Balan: Well, when Rhea went to work for him, she went as his assistant. She probably did a lot of running around doing a variety of things. There’s an open question … because Duranty was an unseemly character. He was into drugs and orgies and all kinds of things. He had all kinds of affairs with young women. In some cases the women threw themselves at him. It’s unclear whether she got the job because she submitted to his advances or not. But she used the opportunity to learn Russian. She had a gift for languages and she also learned how to craft newspaper stories from him.

After nine months working for him, she was in a position where she could start selling her own stories to newspapers, chiefly the London Daily Express, which was owned by a fellow Canadian, Lord Beaverbrook. So her stuff started appearing there. But she didn’t get a byline. It was just, “From our special correspondent.” It was never identified with her. But she had to navigate the vagaries of dealing with the Soviet censorship. You had to be very careful with the stuff that you sent out to the country because the censor didn’t like it. You’d get into trouble, they’d cut stuff or they could kick you out.

She was able to do that. So by late 1929 she’s already supporting herself freelancing. She moved in with an ordinary Russian family in what’s called a kommunalka, a communal apartment. There were 14 people living in basically three rooms. She had one room to herself. They shared a kitchen. They shared a bathroom. Of course she could pay in hard currency because she was paid in pounds. And she had access to stores that foreigners could get access to that regular Russian citizens couldn’t. So she was able to help them. But it gave her a sense of how, in this worker’s state, what life was like for an ordinary worker. It was hard. It was brutal. They were living in these horrible conditions.

Pawlina: So she really got a rude awakening.

Jars Balan: It was gradual. And it’s unclear when she began to see the light. She went thinking that, “Well women have achieved equality here, workers are in power here. They’re modernizing. This is the future. Planned economy. This is where the world is going and they’re ahead of everybody.” Gradually she began to realize what a horror story the Bolsheviks were creating there. She decided to make this trip to the far North in 1932. Because of course there were all these reports about how the Soviets were using political prisoners as slave labor in the forests harvesting timber and processing it.

This was a time when Canada was losing its timber market in Great Britain. The Brits were starting to buy a lot of timber from the Soviets because it was cheap. And of course the argument was is that, “Hey, well, of course it’s cheap. They’re using slave labor. How can we compete?” And so Canada, under Prime Minister Bennett, mounted a very fierce campaign. First of all, to try to get the Brits and all the Commonwealth countries just to buy timber from fellow Commonwealth countries and to support each other through trade and not buy cheaper stuff from the Soviet Union.

So when Rhea went and actually saw physical evidence of slave labor being used—political prisoners being used in precisely this fashion—she wrote a series of articles that she managed to get out to the West without going through the censor. When they appeared in the West, this really ticked off Soviet authorities. As well, she eventually ended up writing, as I said, 21 articles about that trip that she made.

One of the places she stopped at was Petrozavodsk which is in Karelia, a historically Finnish part of Russia that the Russians grabbed and still have. She visited with Finns who were there from Canada and the United States, communist Finns who came to help build this wonderful future society. They’d been working in Northern Ontario in the forestry industry and in other places. And went there and worked.

But she describes visiting their communities, but also after Petrozavodsk she took off north to a place called Kem on the white sea. It’s the administrative center for the Solovetsk prison camp. The infamous Solovetsk Island prison that went back to tsarist times. A horrible place to be incarcerated. And they had 10,000 political prisoners there—many of them, Ukrainian intellectuals, artists who had been arrested in 1931, 32 by Soviet authorities.

But she wanted to go to the Island and see for herself. But the Kem was a closed city, they didn’t allow foreigners in, and she had no permission to be there, but she took the train. Because she was totally fluent in Russian and knew how things worked, she got off the train. The train left. It only came every couple of days, so she had a couple of days…she had like three days there before the next train came.

She got a room. And described, in very moving terms, coming to this hotel not in the greatest shape. There’s this sort of sad sack woman mopping up the lobby. She asks, “Where’s the “dyzhurna?” (Where’s the manager?) “She’s upstairs folding linen.” She went upstairs, she showed her a room, which was classic. The bed was like, sagging mattress springs, a broken window, dust. But she thought, great. She was already hardened and used to conditions in the Soviet Union. She was thrilled to get it.

This cleaning lady, who was working in the lobby came upstairs to dust. And Rhea laughed. It was a nervous laugh. She couldn’t believe that she pulled this off. That here she was in this closed city, she had a room, and as she said [later], she gatecrashed Kem. And this woman, who was very sad, said, “Well you go tell the world what’s going on here, how horrible…” There were a lot of women working there whose husbands were in prison. At the train station there were all these women coming hoping to catch a glimpse of their husband, which was hopeless. Husbands who’d been sentenced to 10, 15 years incarceration and everything. It was a really, really depressing place.

She saw gangs of thousands of political prisoners being taken off to the forest to harvest wood and stuff. This is despite the Soviets denying publicly and repeatedly that they used slave labor. So this was very damaging to them that the story got out with an eyewitness account. Rhea got back to Moscow. And two women from Atlanta, Georgia, described as society girls, had decided to go on a great adventure. And their goal was to drive to Moscow and then to drive south through the Central Asian republics of the Soviet Union.

So they arrived in Moscow and they start planning this big trip. They heard about Rhea and spoke to her. So these three women get in this car, that they packed with as much food, spare tires, gasoline, anything that they could get onto this vehicle and headed south from Moscow at the end of August. August 30th. The first night that they spent at Tolstoy’s estate in Yasnaya Polyana. And through Kursk… And they arrived in Kharkiv. And it’s in Kharkiv where they begin to see evidence of starvation.

In the Russian part there’s still food. It wasn’t a problem. You could buy food in the markets and everything like that. They get to Kharkiv and she described seeing hungry people on the streets. While she’s there, this girl comes up to her when she’s in the hotel and introduces herself.. “My name is Ellen Mertza. I lived nine years in New Toronto. My father worked at the Massey Harris factory there. We came here three years ago.” Because under this ambitious five-year plan of Stalin’s, they were throwing up factories everywhere. There’s a big tractor factory that they built in Kharkiv. And so they came to work there. But this woman tells her, she says, “Have you got any bread? We have nothing to eat.” Now, this is a foreign worker pleading for food!

She goes to the factory, actually, in the morning. They left early in the morning before the hotel was open. They drive to this factory, which she describes as a dump. It was supposed to produce 150 tractors a month or something. It was producing one third, or a lot less. And a lot of the tractors were breaking down within a short time of being put into use. Anyways, she couldn’t get in to see the factory. She thought, “Well, there’s foreign workers working here. They always have cafeterias specially for them.” Well, the cafeterias weren’t open. They couldn’t get any food.

She goes to the factory, actually, in the morning. They left early in the morning before the hotel was open. They drive to this factory, which she describes as a dump. It was supposed to produce 150 tractors a month or something. It was producing one third, or a lot less. And a lot of the tractors were breaking down within a short time of being put into use. Anyways, she couldn’t get in to see the factory. She thought, “Well, there’s foreign workers working here. They always have cafeterias specially for them.” Well, the cafeterias weren’t open. They couldn’t get any food.

So they head south of the city, from Kharkiv. And they’re driving past these villages and many of them are empty. There’s nobody in them. The doors are open to the houses, the windows are open, the curtains are flapping in the breeze. And Rhea then goes, “Oh, so this is where these so-called kulaks were expelled from, or people fled from the famine conditions.” They’d already abandoned them, or had been driven out.

Finally they see a village where there’s some activity. They drive in. There’s a bunch of women who are basically selling stuff from their garden. She goes and she wants to buy some milk and some eggs for the women to have some breakfast. First of all, she starts talking to these women. Nobody understands her. She speaks Russian, but they’re all Ukrainian speaking. Finally, there was this kid who translated and explained that, “We don’t want you to give us the eggs and milk. We want to buy some.” But they just said, “The collective has taken all of our livestock, chickens. We have none of that.”

One woman goes, “I live in a neighboring village here. I might be able to scour something up for you.” So she gets in the car with them. They drive a couple of kilometers to this neighboring village and the head of the village comes out. And the village head says, “So you’ve come here from Moscow?” “Yes.” “To investigate conditions.” “Yes.” He says, “Well you tell the Kremlin that we are starving. We are good loyal citizens of the Soviet Union, but they’ve taken everything.” He says, “How are we going to survive the winter once the vegetables from the garden are gone? Who knows?” And he said, “In the spring already of 1932, the children were eating grass like livestock.”

The women started undressing the children, and you could see their distended bellies and their rickety legs. You could see the ravaging effects of famine on them. And she had a hard time looking at this. And she describes in her articles saying, “I had to turn my eyes away. But I made a promise that I was going to tell the world about this.”

From there they continued south. I mean, in a lot of places there weren’t hotels. They’d go to a sanatorium in Slovyansk. And there’s this room with eight or 10 beds. And they’d say, “Well, you can sleep here.” (The three women.) But the other women are really curious to talk to her and say, “So is it true, you are from America? Is it true that workers have meat to eat and white bread?” This is during the depression. Things were hard here, but workers did far better here in the middle of the Depression, even without a job, than ordinary working people did there. These women, some of them were there because they were suffering the effects of malnutrition.

She describes all of this in great detail in this series of articles. They go across the Kuban and she describes watch towers in the corner of these fields. And guys with guns sitting there ready to shoot anybody who tries to sneak in and steal a few grains of wheat. They make it all the way to Georgia, and it’s clear they’re waiting for her. Obviously, the Secret Police. They were going to kick her out. They gave her 24 hours to leave the country. But the British Embassy intervened. They managed to get permission for her to be sent back to Moscow under escort. And she was given two days to pack her belongings and to leave the Soviet Union. While she was packing up, who visits her? Malcolm Muggeridge.

Pawlina: I’ve been speaking with Jars Balan, from the University of Alberta where he is director of the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies and coordinator of the Kule Ukrainian Canadian Studies Center.

In Part 2 of this interview Jars, will tell us more about Rhea Clyman’s reporting on the Soviet Union and the Holodomor. Also, her astonishing courage reporting as a Jewish woman in Nazi Germany.

I hope you find the story of Rhea Clyman as intriguing as we do. Until next time, Shalom!

(Originally published Feb. 27, 2019.)

This episode of Ukrainian Jewish Heritage was brought to you by The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter based in Toronto, Ontario.

Please support our work by purchasing book using our link. There is no additional charge to you but it sends a few cents our way. Дякую! Thank you!

Tune in to the Vancouver edition of Nash Holos Saturdays at 6pm PST on CHMB Vancouver AM1320 or streaming online. As well, the Nanaimo edition airs on Wednesdays from 11am-12pm on air at 101.7FM or online at CHLY Radio Malaspina.