The Jewish population of Ukraine before the Second World War was over 2.5 million. Now the current population is only around 100,000.

A whole world with its very own culture, rules, and customs was decimated in the Holocaust.

Decades later, descendants of survivors, along with friends and supporters, are working hard to piece together remnants of this once vibrant world.

In western Ukraine and other parts of the former Austro-Hungarian empire, many restoration and educational projects are underway. But in eastern Ukraine, not so much.

One man however, has taken on the gargantuan task of cataloguing Jewish shtetls in eastern Ukraine.

Vitali Buryak recently discovered his Jewish roots. In the process, he created a website called History of Jewish Communities in Ukraine.

I came across his website while doing research on shtetls. Vitali, also known as Chaim (his Jewish name), kindly agreed to tell me his story so I could share it with you. Here is part of that conversation.

Pawlina: So first of all, could you tell me about yourself?

Vitali Buryak: My name is Chaim Buryak, I am living in Kyiv. I am 32 years old. My father is Ukrainian and my mother is Jewish. So according to Jewish law, I am Jewish.

Pawlina: Yes.

Chaim: I was born in Prolukhiv. It’s a city in the Chernihiv region. I studied school in Nizhin, where my parents still live. And started my university in Kyiv 16 years ago. And for the last 16 years I’ve been living in Kyiv.

Pawlina. And so what do you do there?

Chaim: I was working in different IT companies, and still working in IT. I’m a software engineer.

Pawlina: So why did you decide to create this website and embark on this ambitious project? Basically you’re doing it as a hobby?

Chaim: Yes, yes. I am doing this in my free time. It’s not much free time, but I’m trying my best. Why I decided [to do this]? Good question! All my life I was interested in history. I read historical books, [but]not Jewish; maybe the first Jewish books which I read was about six years ago. So all my previous years of historical experience was just common history. Also military history.

Pawlina: So what inspired you to do this?

Chaim: One time I visited Israel, as a part of the Taglit program. It’s like a birthright trip that a person can emigate to Israel, or can make a short visit to Israel.

Pawlina: What happened next?

Chaim: A famous genealogist tried to find a person who could be a tour guide in Jewish Kyiv. And he proposed small courses and after these courses a person would be able to provide some tours of Jewish Kyiv for tourists. I decided to join these courses. After this I made the first steps in my Jewishness. Because before I did not know what it means to be a Jew. What is a Shabbos? What is Torah? Who was Moshe? It was like a fairytale for me.

Pawlina? Really?

Chaim: Yes, for sure! I was born into a very assimilated family. I knew nothing about my Jewishness. Full, empty zero!

Pawlina: So how did you find out about your mom then, if your mom isn’t an observant Jew?

Chaim: I always knew that she is Jewish because on my birth certificate it was mentioned. And all my life I knew that my mother is Jewish. But for me it was like a fairytale that you’re Jewish only if your mother is Jewish. That it’s not passed [down] by your father. And I got this information only … maybe seven years ago. Before it was like some kind of mystery.

Pawlina: Oh!

Chaim: And also one guy in Kyiv asked me to fill his website. He asked me to make a small description of the shtetls, anywhere in Ukraine. He gave me a book, and asked me to please put all the information in the book on the website. And he said I’ll give you some money for this. So it was like a job. And I started to read this book. It was 100 Shtetls in Ukraine. But it was really about maybe 20 or 30 shtetls that were described in this book.

Pawlina: Ah.

Chaim: And I started to read about the shtetls. I know that Jews lived in Ukraine. Thousands and thousands of Jews lived in Ukraine, and before the war millions of Jews lived in Ukraine; it was a Holocaust. I know history well. I know about Babyn Yar. But it’s like it was not very close to me. For example, you hear now about some civil war in Syria.

Pawlina: Yes.

Chaim: For me it was the same. So something happened to somebody in this territory, okay fine. But it happened 70 years ago. Why should I feel something about this? For me it was [surprising to learn] that there were places in Ukraine where Ukrainians were the minority and the majority were Jewish. And all the Jewish population disappeared! No Jews are left. Now [you will often find] a small village is inhabited only by Ukrainians but it has some Jewish history.

Pawlina: I see.

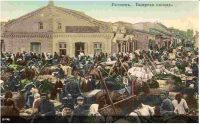

Chaim: And the next step was when I became a tour guide. One tourist from the United States wanted to visit his shtetl, his ancestral town, where his great, great grandparents escaped from 100 years ago. Theoretically, we found it; we Googled it. But there was only one fully Jewish settlement in the Cherhihiv region. It was a small village; just 600 Jews lived there before the revolution, but it was fully Jewish. No Ukrainians lived there. And [when] I googled it I found that a local historian lives there.

Pawlina: Oh, lucky!

Chaim: Ha! Yes! So I called this person and he said that he had researched the local history for the past 40 years, and had spoken with people who knew these Jews very well. So he said, “Come on, Chaim and I will show you all the sites which I know.” And so we visited this shtetl and this local historian showed us all these sites. Like the Jewish cemetery—well the former Jewish cemetery ; it’s a garden now, potatoes are growing there now.

Pawlina: Oh!

Chaim: And he showed the site of the synagogues. Just the site. Nothing is there, just some space between two buildings. And he showed all the Jewish buildings in this building. So this guy from the U.S. was fully satisfied. But for me it was like a shock. I didn’t think that some villages in Ukraine had thus [kind of] history. Before I only read about this in books. But wait. Another story about this trip. This guy, this lawyer from the U.S., wanted to visit two places. The first one was this village, Dmitrivka. Also he wanted to visit Priluki. Priluki is the place where I was born, and my grandma is still living there. I contacted the head of the local Jewish community and he knows my grandma very well. And he showed me placed that I didn’t know about before! In my city, where I was born! My grandma didn’t show me the synagogues, she didn’t show me Jewish cemetery, she didn’t show me the Holocaust killing sites, or the sites of the ghetto. She didn’t show it to me. I walked on this street, I’ve seen these buildings before. But I didn’t know it was a synagogue, for example. And it was like a shock for me.

Pawlina: And so she didn’t tell you anything about your Jewish heritage at all?

Chaim: I did not ask, and she did not tell me. I know that my great-grandma was from a poor family and she was evacuated with her family, all her sisters and my great-great grandparents, to Kazakhstan. That is why they survived and I was born. From Priluki ghetto (during WWII), only around 10 people escaped and I found four or five who survived. From around 1200. So there really was no chance for Jews to survive in Priluki during the Nazi occupation.

Pawlina: Oh wow. Wow. What does the word shtetl mean, exactly? On your website you have a quote there that says: It’s not exactly a town, not exactly a township.

Chaim: Good question. Shtetl is a Yiddish word which means “small settlement.” Something between a village and a city. Because at that time, in the 18th and 19th centuries, Jews lived in these shtetls. They were very crowded. Usually the central street of the shtetl was a whole street of buildings close to each other, without gardens behind them because Jews weren’t allowed to own land. Also Ukrainians lived in these shtetls, but usually Jews lived in the centre, and Ukrainians lived in the suburbs. Anyway, the places where the majority were Jews were not large; the whole populations were less than 10,000, less than 5,000 people. And I created a list of settlements where more than 1000 Jews lived. I created this list for each gubernia (province) in Ukraine, and a plan for my research. My plan is very simple: to write at least a small article for each place on my list. And also I am trying to not lose time [writing] on western Ukraine. Because western Ukraine became a part of the Soviet Union only before WWII and Jewish life stopped here only in 1941 during the Holocaust.

Pawlina: In western Ukraine?

Chaim: Yes. And for this period, between the First World War and the Second World War, many Jews emigrated to Israel (Palestine as it was called before), the U.S., Canada, England. They brought [with them] some photos, some books, and wrote many memory books. And western Ukraine is investigated very well. For example if you google about Zlochiv, you will find tons of material. But if you try to google about Dymer , a village near Kyiv about 20 or 30 kilometers away, in the centre of Ukraine, you will find (I think) only my article! I visited Dymer two years ago, I found a local historian, and he showed me the remains of the Jewish cemetery, the killing site … it’s just a field, nobody has marked mass graves there. So hundreds of Jews are still there, and they have planted grain on it. They showed the sites of synagogues, the former Jewish neighbourhood, the last prayer house and we spoke with the owner of this building. He gave us part of the door, with the mark of mezuzah. They cut this part of the door off and brought it to a Jewish museum.

Pawlina: What is it?

Chaim: A mezuzah is a small scroll with the words of Torah. It is really small, around 10 centimeters, not more, which should be put on the right side of the door in any Jewish home. It’s maybe the last material part of Dymer ’s Jewish history. The rest is just photos and memories, but this is a real thing that you can touch. That is why you won’t find shtetls in western regions of Ukraine on my website. I am just trying to describe places which weren’t described before.

Pawlina: Yes, there is a lot of work being done in western Ukraine. But you’re right, eastern and central Ukraine I don’t have much information about.

Chaim: Look, if you check the statistics of the Jewish population before the revolution, you will see that for example, in the Kyiv gubernia more than 400,000 Jews lived. In the Chernihiv gubernia, around 40,000. So if you move to the east you will see that the Jewish population decreased, decreased, decreased…because you know that Jews in Ukraine arrived from Poland. And most Jewish places in Ukraine were in western Ukraine…Podollia, Volynia, and partially central Ukraine. Eastern Ukraine didn’t have much of a Jewish population.

Pawlina: OK so what you’re interested in is areas that are still undiscovered or under-researched, and there is no information about them.

Chaim: Yes, I only try to search in the internet, and when I see that some place really wasn’t described. For example, the community in Rzhyshchev …. Rzhyshchev is in the central district of the Kyiv region, not far from Kyiv, maybe a half-hour drive. More than 6,000 Jews lived there 100 years ago. No Jews live there now. And if you try to find something about its Jewish history you will find nothing. All this community just disappeared, and that’s all. No traces. Yes, there are some traces in archives in Ukraine. In the Kyiv archives they have tons. And I am not speaking about the number, I am speaking about the weight of this paper. Tons. Tons of documents. Very interesting.

Pawlina: Wow.

Chaim: Yes, they have shtetl maps, surnames, different files And if you have the time, in one month [of research] you could describe a shtetl as if you had lived there.

Pawlina: Wow. Where are they stored?

Chaim: In Kyiv. There are a few archives in Kyiv, and they store this information.

Pawlina: Why is it important for you … essentially these are ghost towns, the shtetls have disappeared … why is it important to you to chronicle that information, compile that information, when there’s nobody there anymore?

Chaim: I don’t know why it’s important for me, because sometimes I feel it is important only for me! To describe the history of a community which will disappear in five or ten years, and no Jews are left there, but this place had some Jewish history, and sometimes it’s three or four hundred years of Jewish history. And it will end in my days. Sometimes I feel that I need to describe it and get it made public. Why it’s so important for me, I don’t know. I sometimes ask myself the question: What’s the sense? What’s the sense to visit it, to spend your time? But I like it. I really like it. I try to spend my vacation on the beach, and I lie on the beach and start to think: What am I doing there? I really don’t like this… I don’t like this beach, I don’t like this food, I don’t like this sun, I don’t like this sea. Better to me, the middle of nowhere. And sometimes it really is in the middle of nowhere. You have very bad roads, some parts of Zhitomyr are even badly inhabited due to radiation-radiative pollution.

Pawlina: Right!

Chaim: And you went to this place and start to speak with some old people: Do you remember something about the Jews who lived there? And ha ha, sometimes I think that there is something not quite normal with me!

Pawlina: Haha!

Chaim: Yes, it’s very funny. But I really like it. I don’t know why I like it. And it’s how I spend my free time.

Last Jewish shop in the center of former shtetl Pyatigory. Now it is a village of Tetiev district, Kyiv region.

Pawlina: It’s important to you! It interests you and something is … it’s important to you.

Chaim: Yes, but sometimes I recognize that it’s important only for me. No other people care about this old village. And even the village will disappear soon. In some places, where the population 100 years ago was 2000 people, and now, it’s 200 people. And you see that it’s only the statistics, the 200. In reality it’s 50 people live there. And you see that it will disappear soon. It’s not like a Jewish place that will disappear soon. It’s like a Ukrainian place will disappear soon.

Pawlina: Oh. Ok I understand. They’re going to become ghost towns eventually.

Chaim: Yeah, yeah.

Pawlina: And you’re not a historian by trade, but you have this mad passion for history. So that’s wonderful. And you know, it’s lonely work that you’re doing, but I don’t think that it’s frivolous, and I don’t think it’s meaningless, certainly. I think it has great value and somebody will thank you for it. So what are you looking for, for help from the public?

Chaim: Just materials, and not more. This research doesn’t need much money. Photos, and maybe some memories, some books about the shtetl, because some books were printed in very small circulation, and you cannot even find these books on the internet. So I’m really seeking information from them, from family photos, any memories from pre-revolution life.

Pawlina: How would they get them to you?

Chaim: Like you found me! Via the website or Facebook. I have a Facebook group, also another very nice page on Facebook, Tracing the Tribe, with more than 20,000 who are searching for their Jewish roots.

Pawlina: Ok. And do you have another site?

Chaim: I have my own group, JewUA dot org Shtetls in Ukraine, and a website JewUA dot org.

Pawlina: Well Chaim, it’s been a pleasure talking to you! Thank you so much.

Chaim: Thank you too!

Pawlina: Dobranich! Bye bye.

Chaim Buryak, creator and curator of the website Jew UA.org. You can find him there and also on Facebook. Just search for Jew UA.org, and also for Tracing the Tribe and Shtetls in Ukraine.

This is Pawlina, producer and host of Nash Holos Ukrainian Roots Radio. I hope you enjoyed this episode of Ukrainian Jewish Heritage. Thanks for listening. Until next time, Shalom!

Ukrainian Jewish Heritage is brought to you by The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter based in Toronto, Ontario. To find out more visit their website (here) and follow them on Facebook and Twitter.

![]()

Tune in to Nash Holos Ukrainian Roots Radio in Vancouver on Saturdays at 6pm PST on CHMB Vancouver AM1320 or streaming online, and in Nanaimo on Wednesdays from 11am-1pm on air at CHLY 101.7FM or streaming online at CHLY Radio Malaspina. As well the International edition airs in over 20 countries on AM, FM, shortwave and satellite radio via PCJ Radio International.

The interview you did with Chaim Buryak in 2018 is the first Nash Holos segment I heard. It had an enormous impact on me. Nash Holos became my favorite radio show!

The terrific follow-up of the Lost Shtetls of Ukraine from this past summer is an excellent compliment to the 2018 interview with Chaim (21:50 mark ):

https://shows.acast.com/nashholos/episodes/nash-holos-vancouver-2020-0829